As an artist, Daniel Brush had always been intrigued by the color used by French Impressionist painters, and particularly by Monet’s palette of light-infused hues of muted pinks, cerulean blues and cadmium yellows. As ever Brush needed to investigate and research this in depth, and he and his wife Olivia travelled to Europe, taking several trips focused primarily on understanding this very specific use of color. They went to Arles, Rouen, Giverny and spent several months living in Paris. However, as much as Brush wanted to embrace Monet, he used to say, there was always a “push-back” because he disliked pasty oil paint. In their search for an understanding of Impressionist color, specifically Monet’s approach to color, Daniel and Olivia had gone to see actual haystacks

in fields near Giverny. The visit confirmed Daniel’s dislike. “Even with all those classical glazing techniques, the paintings did not have the majesty of the natural light bathing the haystacks, the meules de foin, that we went to see in the fields.”

Back in the studio, in Manhattan, quite by chance a friend, an art collector, came to visit one day, and showed them both an 8 x10” transparency of a Monet painting he had recently acquired. They held the transparency up to the light, and in that moment, Brush says, he fell in love with Monet’s “thinking.” He explained, “I liked Monet’s work when I saw it as a transparency with the light shining through.” Daniel Brush saw the light.

From then on, Brush was determined to paint in light. Light was one of Brush’s enduring preoccupations: the nature and science of light, meaning, the responses it generates, the light within a gemstone, the light that Brush was uniquely able to coax from steel or aluminium, and the drama of light generated by his engraving. it is the lustre of gold, of the sun, the light of the divine; the light in the eyes of someone who sees a Daniel Brush jewel for the first time.

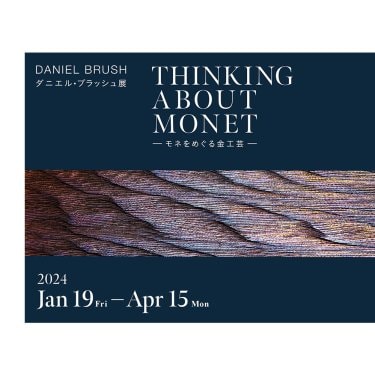

Brush thought back to his high school and college physics lessons, when he saw how a light beam could be bent and refracted through the use of a diffraction line grating, with its thousands of mechanically-scored lines per inch. He thought about the perfect marriage of color and light, the two most powerful emotional triggers in a jewel or gem. Inspired by the scientific principle of the diffraction grating, which can break a beam of light into many wave lengths that manifest as different colors, Brush began to hand-engrave a series of sculptures. He engraved them with a multitude of lines, so fine and engraved at such minutely specific angles that they too broke the light, so that what is refracted back to the viewer’s eye are colors; warm, deep, emotionally-stirring colors created not by oil paint, or watercolor, or pigment but by light.

Illuminating Daniel’s affinity to light and color, the Thinking About Monet series also distils his intense relationship with Japan and Japanese art. It hints at Japonisme, the late 19th century obsession with all things Japanese, that played a major role in shaping Impressionism. It was the revelation of the artistry of Japanese woodblock prints, in the Ukoyo-e style, their stylisation and compositions, that exerted such a powerful influence on artists, including or especially Monet, who owned a collection of Ukoyo-e prints.

Daniel Brush pondered and challenged the connection between art and jewel, while taking it to an entirely new level, of artistry, message, meaning and emotional impact, all embodied in Thinking About Monet.

Vivienne Becker, jewelry historian