Immerse yourself in the world of the exhibition "Paris, City of Pearls".

Extend your discovery with the exhibition Visual Guide.

Immerse yourself in the world of the exhibition "Paris, City of Pearls".

Extend your discovery with the exhibition Visual Guide.

All molluscan shellfish are capable of producing pearls of calcium carbonate. But their quality depends on the species as well as conditions such as temperature, salinity and the animal’s nutrition. The finest pearls in jewelry generally come from sea oysters from hot regions on either side of the equator.

No matter how widespread, the famous theory that a grain of sand can trigger biomineralization is not grounded in any scientific reality, nor has a grain of sand ever been found inside a pearl.

While the causes of pearl formation (a virus? bacteria?) continue to elude us, pearls result from the displacement of epithelial cells responsible for secreting the shell into the connective tissue of the mollusk’s mantle. Historically, and according to international standards as well as French law, the word “pearl” used on its own in the jewelry world signifies a natural pearl. This nomenclature emphasizes the fact that these pearls are formed without human intervention. But it was not really necessary to make this distinction in France prior to the 1920s and the gradual arrival of cultured pearls on the Parisian market.

However fanciful, George Bizet’s opera The Pearl Fishers (1863) takes place in the Indian Ocean, a long-established source of pearls—the Gulf of Mannar in particular—cited by Pliny the Elder in Book IX of his Natural History.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the pearl was closely tied to Orientalism in painting and theater.

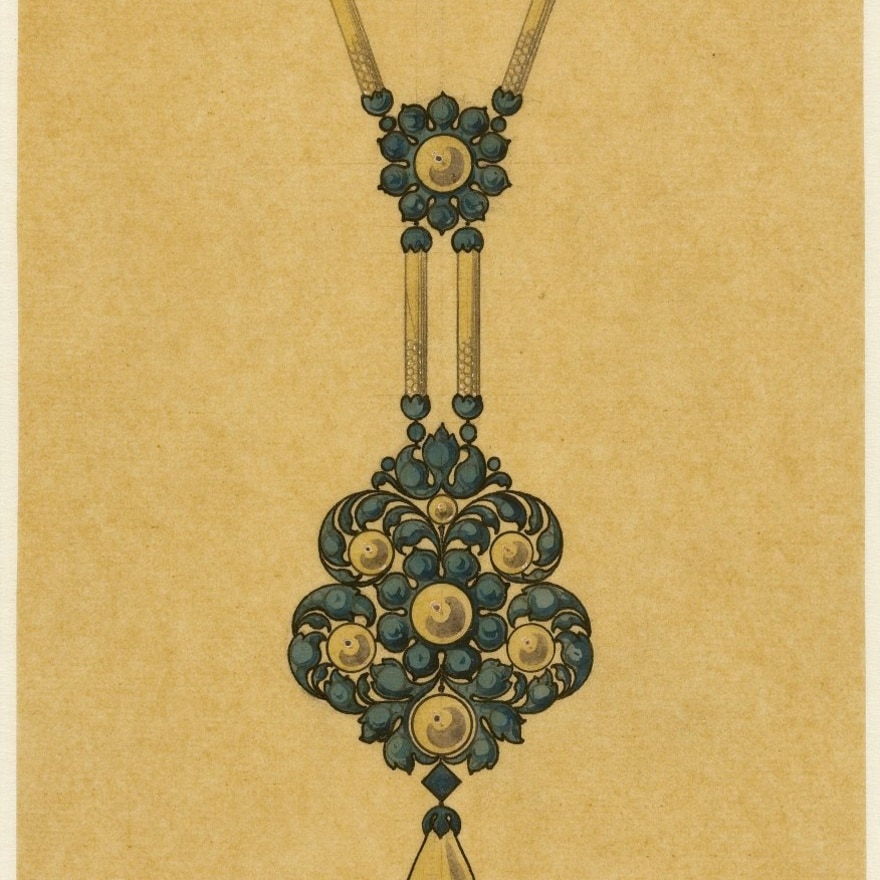

Recognized since Antiquity, the Arabo-Persian Gulf region remained a prime source for pearls, to the extent that this specificity was inscribed on geographical maps as early as the Renaissance. Its western shore was notable for its large number of pearl oyster beds. The esteem of Westerners for Gulf pearls has never wavered, despite the discovery of other sources and other pearls over the centuries, particularly in Central and South America.

A series of auctions organized at the start of the twentieth century speaks to the constantly increasing value of pearls.

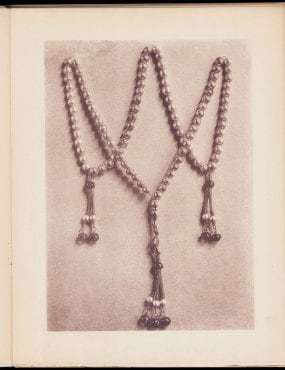

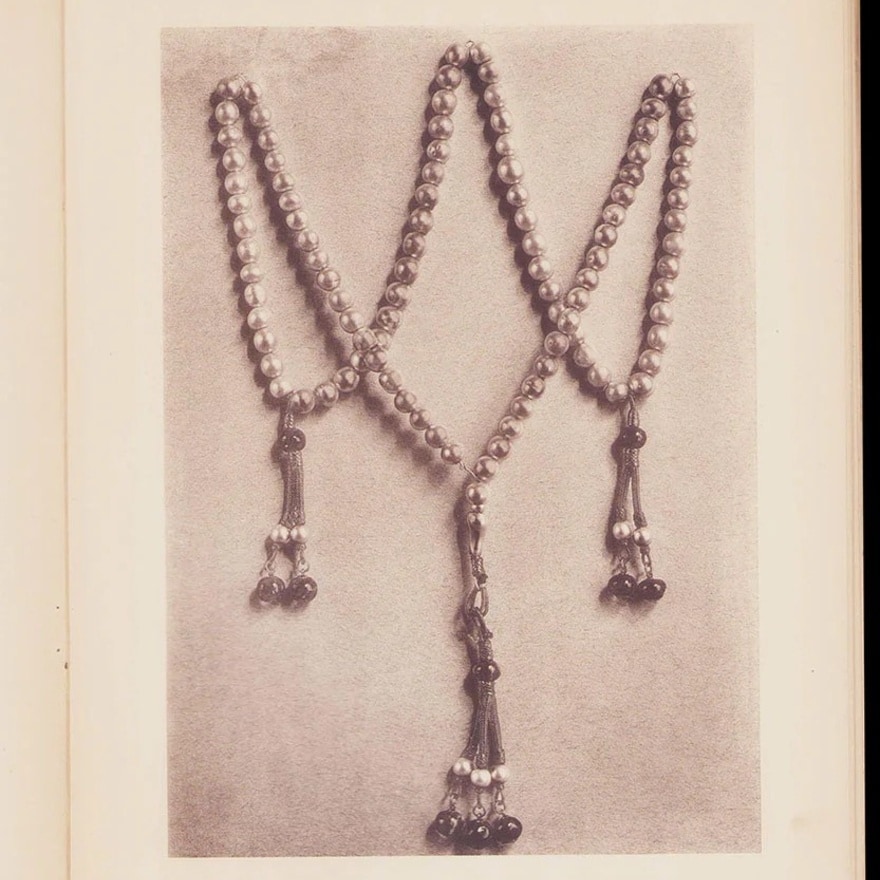

Three auctions in particular made headlines in Paris: the 1904 sale of the jewels of Princess Mathilde Laetitia Wilhelmine Bonaparte, including pearls given by Emperor Napoleon I to her mother, Katharina of Württemberg, Queen of Westphalia, for her wedding; the 1909 sale of the collection of historian and patron Alexandre Alexandrovich Polovtsov, during which a four-strand pearl necklace reached the million-franc threshold for the first time; and the record-breaking sale three years later of the jewels of Abdulhamid II, one of the last sultans of the Ottoman Empire.

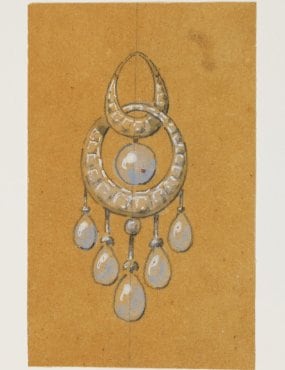

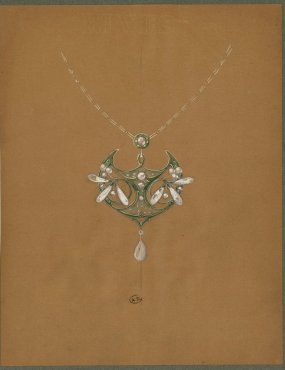

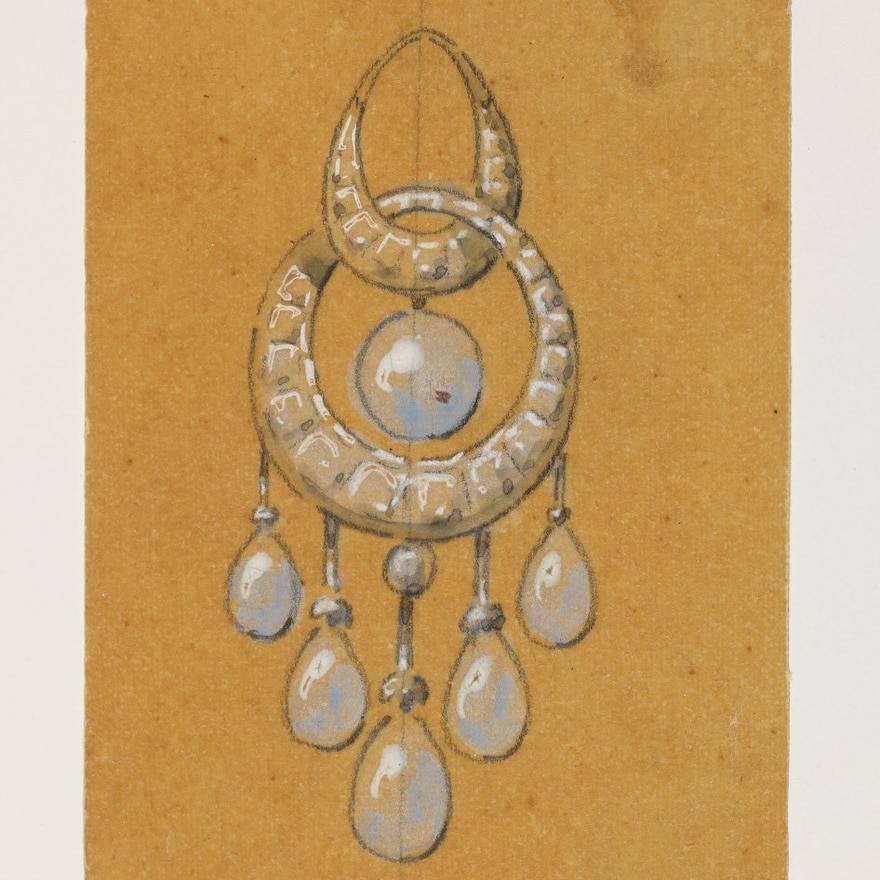

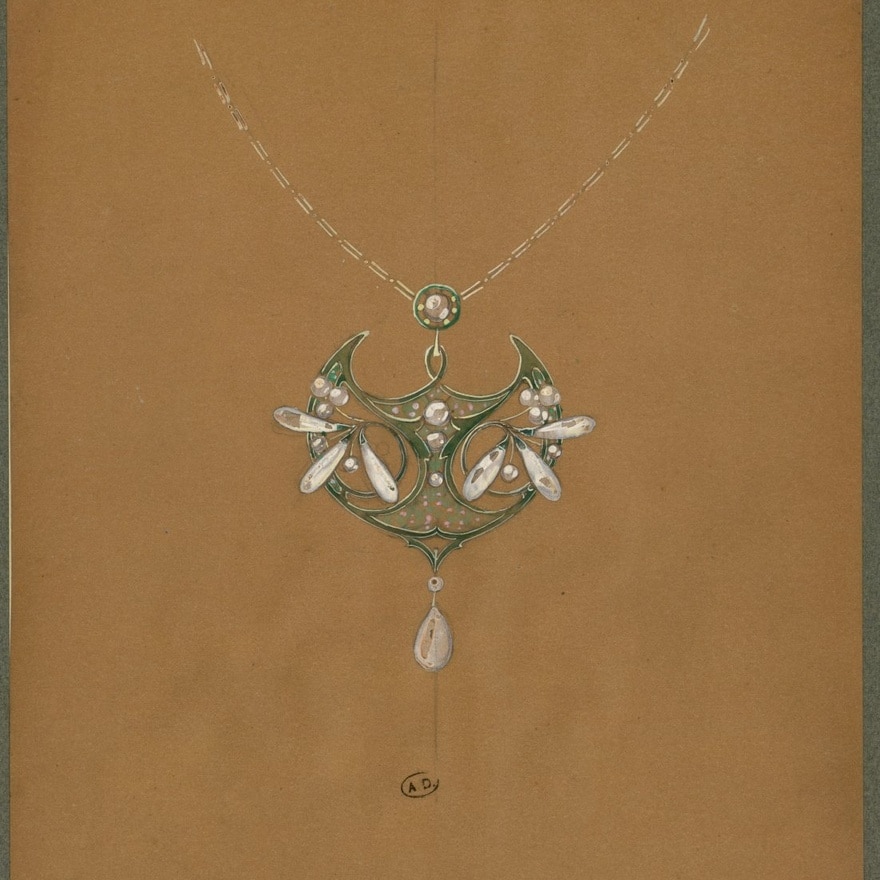

Pearls abounded in the showcases of brothers Paul and Henri Vever, the ingenious René Lalique and the very innovative Georges Fouquet, as well as all the other representatives of what would in France later be called Art Nouveau. Inspired by Far Eastern forms and nature, they were particularly interested in the most baroque varieties of pearls. They did not hesitate to favor pearls shaped by Mississippi mussels over traditional Gulf pearls. Other pearls of unusual shapes and colors were also very popular among the different players of the Parisian nightlife scene.

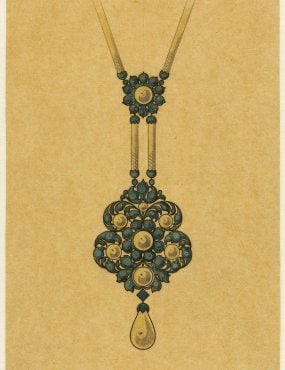

The great jewelers of the Rue de la Paix and Place Vendôme avidly sought out the finest pearls, pairing them with platinum and diamonds. It was the Belle Époque, when jewels were notable for their whiteness, luster, lightness, geometry and aristocratic inspiration. The heads, ears, necks and wrists of the elite—queens, first ladies and courtesans—and their entourages were embellished with pearls. The most coveted pearls were small specimens from the Gulf, recognizable for their creamy and sometimes slightly pinkish hue.

Marked by the explosion of the Parisian pearl market, the 1910s long remained a blind spot in the study of the decorative arts, overshadowed by the blossoming Art Nouveau movement in Europe and the advent of what would come to be known as the Art Déco style, popular during the interwar period.

But it is a period that begs to be studied in its own right, even if only to better appreciate the talents of a young group of Parisian dandies and artists who shared a passion for pearls, calling themselves the “Knights of the Bracelet.”

At the time, the Rosenthal brothers, who were among the very first Parisian pearl merchants to travel to Bahrain, reigned supreme in the region. But in 1912, when jeweler Jacques Cartier journeyed to the Gulf region, he was hailed as a veritable dignitary.

The value of pearls in France may have reached its highest point, but it was in the U.S. that the demand for pearls was strongest. In 1917, Pierre Cartier acquired his mansion on New York’s Fifth Avenue in exchange for a double-strand pearl necklace, of 65 and 73 pearls, respectively.

After World War I, the pearl frenzy continued to thrive in Paris and the Gulf region. Merchants like Léonard Rosenthal, Jacques Bienenfeld and Mohamedali Zainal Alireza found themselves at the head of commercial empires, while new players were also emerging, attracted by the rampant growth of a seemingly unshakable market.

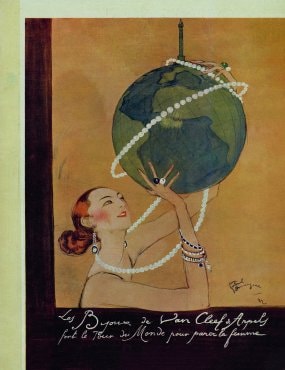

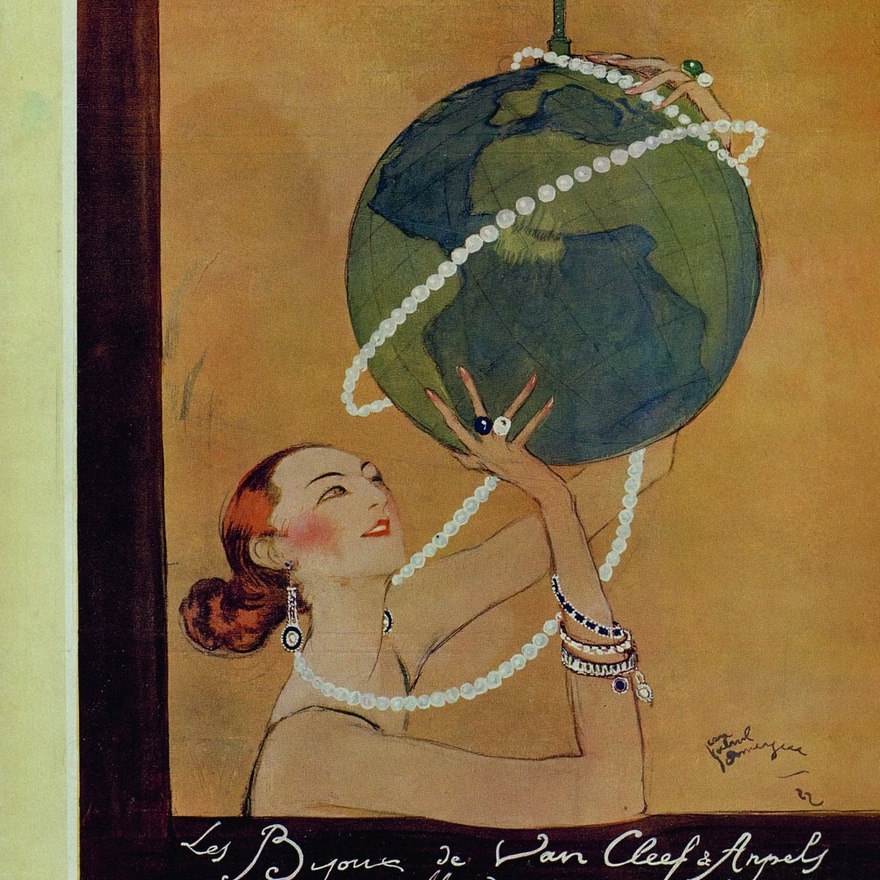

Held in Paris from April to October 1925, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts gave fresh impetus to the “pearl mania” sweeping through Paris at the time.

While the arrival of cultured pearls from Japan was seen by some to mark “the end of the age of the Parisian pearl,” this statement needs to be qualified. For while the demand for natural pearls continued to increase, the supply was constantly declining, as pearl fishing was abandoned in the Gulf of Mannar and pearl production gradually decreased in the Gulf region. The public began denouncing the highly precarious circumstances in which pearl fishers lived and worked. The reign of the Parisian pearl was weakened by the economic crisis of 1929, only to decline even further with World War II and the deportation of Jewish merchants from Rue La Fayette.

World War II dealt a fatal blow to trade between France and the Gulf region. Many French merchants reoriented their activity around cultured pearls, starting with the Rosenthals, who continue the adventure to this day. . . in Tahiti! To prevent the disappearance of the region’s typical black pearls, which suffered from overfishing in the late 1950s, the French and Japanese joined forces to set up pearl farms in the region. While cultured pearls remained highly popular, especially among younger generations, the natural pearl trade left Paris.

Pearl fishing zones are now highly protected and controlled: only a tiny number of “new” natural pearls appear on a market that is for the most part sourced from family collections and pearls unset from antique jewelry. But in Paris and around the globe, natural pearls continue to inspire the jewelry elite.

The start of the twenty-first century saw the emergence of various contemporary art initiatives between France and the Gulf region. Focused on the pearl, they breathe new life into long-standing cultural and human adventures, while also serving to preserve their memory.